Channa orientalis Bloch & Schneider 1801

Colin Dunlop

Some snakeheads in the Channa genus are real giants and some like Channa micropeltes, C. argus or C. maruliodes can get to about a meter long. Many of the giant species are easy to get in the aquarium hobby but might not be so suitable unless you have an equally giant tank. Channa orientalis however, is a dwarf by comparison and has an average size of a more manageable 10 cm. This dwarf snakehead comes from South Western Sri Lanka and the Kottawa Forest. You may see that there are currently a few variants within the species and the one I have kept is known as “Kottawa Forest A”. You may also come across “Kottawa Forest B” and if you have both variants then it is better to keep them separate.

The natural habitat of C. orientalis is the slow moving streams and blackwaters of the rainforest. They have been known to survive in quite harsh conditions and – like other members of the genus – are famous for being able to cross areas of damp land in search of new water. They can breathe atmospheric air just like gouramis and Bettas.

I originally started with eight specimens that I got from Paul Jordan, who is a friend and fellow member of the Anabantoid Association of Great Britain (AAGB) and at the time they were around 4 – 5cm in length. They were put into a 60 x 30 x 30 cm tank that was decorated with some clay pipes, plastic plants, coconut-shell caves and the filtration was supplied by an air-operated sponge filter. The pH could range from 5 to 7 and this is because the local tap water is so soft that the pH can drop quite rapidly. My fish were given a tropical temperature of about 24- 25°C as unlike some other members of the genus, C. orientalis are a true tropical species and not subtropical as say Channa bleheri. It is of paramount importance to ensure that you cover the aquarium; all species of Channa can jump out of any gaps.

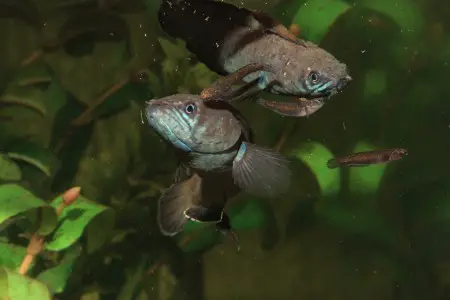

My new snakeheads were fed on a good variety of food including a staple diet of granule fish-food supplemented with frozen bloodworms, grindalworms and earthworms. They grew quickly under this regime and with regular water changes they were getting near breeding size within only a few months. By the time the largest got to be about 8 cm long they had started to show some really nice blue colours across the fins and there was a slight increase in their aggressiveness towards each other, whereas up until this point they were very peaceful.

The main problem I had was that I couldn’t see any sexual dimorphism between the fish to split them up into pairs so they remained as a group. However, it wasn’t too long before the fish started to solve the problem for me and on two occasions a fish that was perfectly healthy one day was found tattered, torn and dead the next. This apparently meant that a pair had started to form and the only way I knew this was because the couple could be seen embracing around each other’s bodies in an “S” shape. I eventually managed to catch the pair together and put them in their own tank leaving the rest to hopefully sort out another pair. Their new tank was a 60 x 30 x 30 cm and was again decorated with pipes and caves and a thin layer of fine sand for the substrate, but with much disappointment – nothing happened.

Some months later I had a visit from Paul and for the first time in my life I was told that my tanks were all too clean! He looked at all my Channa tanks then decided that it was all the water changes I was providing that was putting them off breeding. I was a tad sceptical at first, but after an epiphany of sorts, I decided to give it a try and listen to the experienced Channa breeder and everything I did next just seemed to be so against the grain for “normal” fishkeeping.

Firstly, I added some garden soil. I have a fairly organic garden with nothing in the way of herbicides or pesticides, so I threw in four handfuls of soil and removed the filter. I left the temperature as it was and within a day the clay-heavy soil had settled to the bottom of the tank leaving what was actually quite a pleasing effect as it looked like a natural pond substrate. The fish seemed quite contented to be rooting around in the soil, even if I was worrying about what might be happening to the water chemistry. However, there was barely any registering of ammonia on a liquid test-kit, despite the fact there had been such a sudden addition of organic material. I wouldn’t recommend this procedure for any other genus of fish, though.

Within days of the “tank-dirtying” the fish were embracing again and after a week the male appeared from a cave with a bulging throat, which meant he was brooding some eggs. Unfortunately he ate this batch of eggs, as some mouthbrooders do during their first attempt. Then he ate the second, third and fourth broods of eggs as well. Eventually patience prevailed and he held full-term and I used a torch to make out some wrigglers hidden away in a clay pipe.

The actual incubation period of the eggs and fry being held seems to vary between individuals and the environmental conditions. From speaking with other people it seems that they can eject fry after as little as three or four days or hold them for as long as ten.

For rearing C. orientalis fry, all we have to do is sit back and feed the adults and let them do all the work. The female feeds the fry by circling over the top and laying eggs, which shower them with a meal. The eggs are small compared to the eggs released during spawning but the fry gorge until their bellies are bulging. With the first brood I removed the fry from the parent’s tank as soon as they were looking for food by themselves and I got eleven young fish from this spawning but it seems that the parents can produce more as they become more experienced. The fry were fed the same food as their parents from about 15mm in length.

When I noticed that the male was brooding again I watched with interest as he started to release small fry, which appeared to be leaving via his gills. I counted over fifty fry this time but about three days later I could see that he had a bulging throat again. I wrongly assumed that the adults had spawned again and tried to catch some of the fry that were free swimming and put them in another tank in case the adults turned on them. I was then surprised to see that after a couple of days his throat was back to normal size and there were lots of large baby fish in the tank again. The male must have collected lots of the fry in his mouth where he kept them for a few days longer.

The most important part of this observation is that even although the fry that were removed from the tank early have been fed very well, they are at least 25% smaller than their siblings who are still in with the adults. I would put this difference in growth rate down to the fact that the babies in the tank with the parents are being fed by the female and her infertile eggs. In the future I think I will leave the fry with the parents until they are about 3 to 4 cm in length.

Thanks go to Paul Jordan for the initial stock of snakeheads and for the help in breeding them.

Channa orientalis FAQ

Q. Can these fish be kept in a community tank?

A. Yes, as long as the tank is large enough and ensuring that the other fish are too large to be eaten. However, if a pair forms and they want to breed then they may be more aggressive.

Q. Are they easy to find in the hobby?

A. They are occasionally available for sale but tend to command prices of £50+

Q. Do I need a filter to keep these fish?

A. Assuming that you have only got C. orientalis in the tank and that it is a large enough tank then no. In fact, it would seem that many species in the Channa genus really do not like regular partial water changes or water which is kept too clean. The best method for keeping them would seem to be a heavily planted tank with little or no filtration. Yes, this does seem to go against the grain for “normal” fishkeeping!

Q. I have heard that there is to be an outright ban of all wild caught species of Channa being imported, is that correct?

A. Yes, snakeheads are listed as one of the species to be banned from import under European legislation to help stop the spread of Epizootic Ulcerative Syndrome (EUS). If this is the case then snakeheads will become very rare in the hobby because most seen for sale in shops are wild caught animals and there are only a few people actively breeding them. There is no time scale available for the ban at the present time. In Scotland, all species of snakeheads already require a license to be kept.

Q. Are there other small species of snakeheads available?

A. Yes, although not as small as C. orientalis, there are others to look for such as gachua, pulchra, ornatipinnis, and bleheri but these are sub-tropical species and should not be kept long term in tropical aquariums.

Category: Articles, Freshwater Fishes | Tags: aquarium, breeding Channa, Channa, Channa orientalid, snakehead | 2 comments »

May 20th, 2012 at 1:42 pm

Superb article Colin, thanks for sharing it with SF 🙂

February 2nd, 2013 at 6:44 pm

[…] damage–digging or eating. I had to look up your Channa on Seriously Fish, a great article at https://www.seriouslyfish.com/channa-…chneider-1801/ My only suggestion is to make the cap deeper, maybe 2"-3", and let the plants root in […]