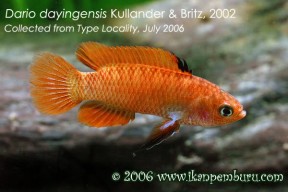

Dario dayingensis

Etymology

Dario: derived from the specific epithet of the type species, dario, which in turn is from its Bangla name, Darhi.

dayingensis: named for the Daying River where the species was discovered.

Classification

Order: Perciformes Family: Badidae

Distribution

Type locality is ‘Small stream tributary to Da Ying Jiang River, upstream end of Bing Han Cun Village, Jiu Cheng Town, 24°45’50″N, 98°8’54″E, Irrawaddy River drainage, Ying Jiang County, Yunnan Province, China’, and it has also been collected in Tenchong County slightly further north.

The Daying is a major tributary of the Irrawaddy/Ayeyarwady river system.

Habitat

The type locality is a small (~ 2 m wide), shallow (< 30 cm deep) stream running through agricultural land at just over 900 m AMSL.

The water flows quite swiftly over a substrate of rocks, sand, leaf litter and mud, and from photos it appears that marginal vegetation provides a degree of cover, with D. dayingensis tending to congregate among submerged riparian vegetation.

The holotype was collected in 1995 and at that time occurred alongside Lepidocephalichthys berdmorei, Devario apogon, Channa gachua, plus the introduced cyprinids Rhodeus sinensis and Abbottina rivularis and poeciliid Gambusia holbrooki.

In 2006 an unidentified barb and non-native Monopterus albus and Oreochromis mossambicus (tilapia) were collected in addition to the above.

Thanks to Zhou Hang.

Maximum Standard Length

25 – 35 mm.

Aquarium SizeTop ↑

A pair or small group with a male and several females can be housed in an aquarium with a base measuring 45 ∗ 30 cm or more.

Maintenance

Best-maintained in a well-structured arrangement with plenty of cover.

A soft substrate is preferable although fine-grade gravel is acceptable, while ideal plants include Cryptocoryne spp. or those that can be grown attached to the décor such as Microsorum, Anubias, or Taxiphyllum species.

The latter is particularly useful as it’s also an ideal spawning substrate, and driftwood branches, floating plants and leaf litter can all be used as well.

Water Conditions

Temperature: It is subject to seasonal temperature fluctuations in nature and is comfortable within the range 59 – 77°F/15 – 25°C with even greater extremes being tolerated for short periods. In many countries/well-insulated homes it can be therefore maintained without artificial heating year-round.

Higher temperatures are known to stimulate spawning activity meaning a heater will be required if you want to breed the fish outside of spring and summer months though. Set it to around 20 – 24 °C for long-term care and breeding.

pH: Prefers neutral to alkaline water with a value between 6.0 – 7.5. At the type locality the pH was 6.2 in July 2006 (Z. Hang, pers. comm.).

Hardness: 18 – 90 ppm

Diet

Dario species are micropredators feeding on small aquatic crustaceans, worms, insect larvae and other zooplankton.

In captivity they should be offered small live or frozen fare such as Artemia nauplii, Daphnia, grindal, micro-, and banana worm.

They’re noted as somewhat shy, deliberate feeders (see ‘Behaviour and Compatibility’) and it’s also important to note that all badids develop issues with obesity and become more susceptible to disease when fed chironomid larvae (bloodworm) and/or Tubifex so these should be omitted from the diet.

Behaviour and CompatibilityTop ↑

Given its rarity the emphasis should be on captive reproduction and we strongly recommend maintaining it alone.

It’s not a gregarious fish as such and rival males can be very aggressive towards one another, especially in smaller tanks.

In these cases only a single pair or one male and several females should be purchased but in roomier surroundings a group can coexist provided there is space for each male to establish a territory and plenty of broken lines of sight.

Thoughtful placement of caves and boundaries can help tremendously in this respect so don’t be tempted to cluster all available spawning sites in one area of the tank, for example.

If you do intend to house it in a community tankmates must be chosen with care.

It’s slow-moving with a retiring nature and will easily be intimidated or outcompeted for food by larger or more boisterous tankmates.

Peaceful, pelagic cyprinids such as Microdevario, Boraras, Trigonostigma or smaller Rasbora species make good choices as do diminutive loaches such as some members of the genus Petruichthys.

Sexual Dimorphism

Males are far more colourful and develop extended pelvic, dorsal and anal fins than females as they mature.

In addition females are smaller and possess a noticeably shorter, stumpier-looking body profile then males.

Reproduction

Likely comparable to other members of the genus which are substrate-spawners forming temporary pair bonds.

Other fishes are best omitted if you want to raise good numbers of fry, although in a mature, well-furnished community a few may survive to adulthood.

Either a single pair or a group of adults can be used but if using multiple males be sure to provide each with space to form a territory with around 30 cm² per individual adequate.

One male will usually become dominant meaning the others will not be involved in breeding.

Water parameters should be within the values suggested above and the fish conditioned with plenty of live and frozen foods.

As they come into breeding condition males will begin to form territories and display courtship behaviour alongside an intensified colour pattern.

This can be prolonged for several days with the female often being chased away then courted again minutes later.

The male will make a non-aggressive approach towards the female and appear to ‘invite’ her into the centre of his territory, and if ready to spawn she will follow.

The act itself is over in just a few seconds with eggs being scattered in a random fashion on the underside of a solid surface such as a plant leaf.

Post-spawning the female is ejected and the male takes sole responsibility for the territory.

If you want to maximise the numbers of fry raised now is the time to either remove the medium to a container containing water from the spawning tank or the adults as the fry will be preyed upon once hatched.

The incubation period should be 2-3 days after which the fry may need up to a week to fully absorb the yolk sac.

They are very small indeed and will require an infusoria-type diet until large enough to accept microworm, Artemia nauplii, and suchlike.

NotesTop ↑

This species has not appeared in the ornamental fish trade to date though has been maintained by a handful of private collectors and enthusiasts.

It was known for some years prior to description and identified as Badis dario (as Dario dario was known at the time) but is actually much closer to D. hysginon.

It can be told apart from D. hysginon by possession of 24-25 scales in the lateral row (vs. 23, rarely 22 or 24), usually 9½ scales in the transverse row (vs. 8½), usually 26 vertebrae (vs. 25), and by the upper jaw containing palatine teeth (vs. absence of palatine teeth).

Dario currently contains five species, of which four are considered miniature species since they do not exceed 26 mm in standard length (SL).

The fifth, D. urops, not only grows larger, to at least 28.0 mm SL, but occurs in southwestern India whereas the others are native to the Brahmaputra, Meghna, and Ayeyarwaddy river systems in northern India, Myanmar, and southwestern China, and this raises interesting questions regarding their biogeography.

In addition, D. urops lacks some diagnostic characters of Dario and thus may represent the sister group to other members of the genus, though this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Prior to 2002 the family Badidae included just five species but an extensive revision paper published that year contained descriptions of ten new species along with the genus Dario of which the former Badis dario was designated type species.

Dario is most easily distinguished from Badis by the small adult size of member species, predominantly red colouration, more extended first few dorsal rays and pectoral fins in males, straight-edged (vs. rounded) caudal-fin, lack of visible lateral line and less-involved parental behaviour.

Badids have historically been considered members of the families Nandidae or Pristolepididae and it was not until 1968 that Barlow proposed a separate grouping for them.

They share some characteristics with anabantoids, nandids and channids, perhaps most notably the typical spawning embrace in which the male wraps his body around that of the female.

More recent studies have concluded that this procedure is an ancient trait inherited from a common ancestor to all these families.

All Badis, Dario and Nandus species were found to share a uniquely bifurcated (split) hemal spine on the penultimate vertebra and this may provide evidence that the group is monophyletic (Kullander and Britz, 2002).

The family Nandidae is currently restricted to include only Nandus species and it’s separated from Badidae by differences in morphology and egg structure with their phylogenetic relationships yet to be studied in detail.

References

- Kullander, S. O. and R. Britz, 2002 - Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 13(4): 295-372

Revision of the family Badidae (Teleostei: Perciformes), with description of a new genus and ten new species. - Britz, R. and S. O. Kullander, 2013 - Zootaxa 3731(3): 331-337

Dario kajal, a new species of badid fish from Meghalaya, India (Teleostei: Badidae). - Britz, R., A. Ali and S. Philip, 2012 - Zootaxa 3348: 63-68

Dario urops, a new species of badid fish from the Western Ghats, southern India (Teleostei: Percomorpha: Badidae). - Rüber, L., R. Britz, S. O. Kullander and R. Zardoya, 2004 - Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32(3): 1010-1022

Evolutionary and biogeographic patterns of the Badidae (Teleostei: Perciformes) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence data.