Rhinogobius nantaiensis

Etymology

Rhinogobius: from the Greek rhinos, meaning ‘nose’, and the generic name Gobius.

nantaiensis: derived from the Chinese Nan-Tai, meaning ‘southern Taiwan’.

Classification

Order: Perciformes Family: Gobiidae

Distribution

Unclear. This species is imported in mixed batches with the near-identical congener R. candidianus which is distributed throughout northern and western Taiwan.

R. nantaiensis sensu stricto is not supposed to occur with R. candidianus in nature, and is officially known only from tributaries of the middle and upper Tzengwen and Kaoping river river basins which drain the southern part of the island.

Habitat

Presumably inhabits smaller rivers, tributaries and streams with substrates of gravel, rocks, boulders, and exposed bedrock which undergo seasonal variations in water flow rate, depth and turbidity.

Southern and western Taiwan has a subtropical monsoon climate characterised by high temperatures and humidity with massive rainfall and tropical cyclones in summer with average annual air temperatutes of 22-24°C/71.6-75.2°F, though in winter it typically drops below 20°C/68°F.

The balitorid loach Sinogastromyzon nantaiensis has an identical natural range and is presumably found in some of the same habitats.

Maximum Standard Length

50 – 55 mm.

Aquarium SizeTop ↑

An aquarium with base dimensions of 60 ∗ 30 cm is large enough to house a small group.

Maintenance

Not difficult to maintain under the correct conditions; we strongly recommend keeping it in a tank designed to simulate a flowing stream with a substrate of variably-sized rocks, sand, fine gravel, and some water-worn boulders.

This can be further furnished with driftwood branches, terracotta pipes, plant pots, etc., arranged to form a network of nooks, crannies, and shaded spots, thus providing broken lines of sight.

While the majority of aquatic plants will fail to thrive in such surroundings hardy types such as Microsorum, Bolbitis, or Anubias spp. can be grown attached to the décor.

Like many fishes that naturally inhabit running water it’s intolerant to accumulation of organic pollutants and requires spotless water in order to thrive, thus weekly water changes of 30-50% tank volume should also be considered routine.

Though torrent-like conditions are unnecessary it does best if there is a high proportion of dissolved oxygen and some water movement in the tank meaning power filter(s), additional powerhead(s), or airstone(s) should be employed as necessary.

Water Conditions

Temperature: 18 – 28 °C

pH: 6.0 – 8.0

Hardness: 90 – 268 ppm

Diet

Rhinogobius spp. tend to be opportunistic carnivores feeding on a range of small invertebrates, crustaceans and similar in nature.

In the aquarium they should be offered small live or frozen foods such as chironomid (bloodworm) or mosquito larvae, Artemia, Daphnia, Mysis, etc.

Dried foods may be accepted following a period of acclimatisation but should not be used regularly.

Behaviour and CompatibilityTop ↑

Can be kept in a community provided tankmates are chosen with care.

Peaceful, pelagic species which inhabit similar environments in nature such as Tanichthys or Danio species are perhaps the best choices for the upper levels, but we’ve also seen Rhinogobius spp. being maintained alongside barbs, small characids, poeciliid livebearers, etc.

It should not mixed with other Rhinogobius spp., especially closely-related ones such as R. candidanus, since it’s not yet clear if they’re capable of hybridisation.

Other bottom-dwellers can include stream-dwelling gobies from genera such as Stiphodon, Sicyopterus, Sicyopus or Schismatogobius spp., diminutive loaches from genera like Gastromyzon, Pseudogastromyzon, or Acanthopsoides, and in high-turnover set-ups obligate torrent-dwellers like Annamia, Homaloptera, etc.

Avoid those that feed aggressively or are excessively territorial, e.g., many Schistura spp.

Larger fishes are best omitted although in very large set-ups it may be possible to add a few non-predatory, surface-dwelling ones, while the majority of cichlids and other territorial fishes inhabiting the lower reaches should be avoided entirely.

Freshwater shrimp from genera such as Caridina and Neocaridina are also unsuitable as they’re likely to be predated upon.

While males are territorial with one another to an extent serious damage is unlikely provided the tank contains sufficient cover, and in fact they appear to actively require the presence of conspecifics.

Aim to purchase at least two males and as many or more females or the fish may become listless and inactive.

Sexual Dimorphism

Adult males develop an extended, whitish-orange primary ray in the first dorsal fin which is absent in females.

In gravid females the eggs are often visible as a bluish mass inside the fish.

Reproduction

As is typical for the genus eggs are deposited on the ceiling of a cave or crevice and guarded by the male until hatching.

Several potential sites should be offered in the form of rocks (flat slate tends to be easiest to handle, see below), terracotta pipes, plant pots, etc.

A nuptial male will select a site and defend it against other males, but if one is not available may excavate a cave beneath a rock or other piece of décor.

Spawning occurs secretively within the cave, and is usually signified by the pair disappearing from sight for an extended period of time.

The pair may remain inside for 2-3 days with the female ejected once spawning is complete, and they should not be disturbed during this period.

Once the female is seen outside the cave, you can check for eggs by carefully lifting and tilting it without removing from the water.

Inexperienced pairs or males may eat the eggs, attach them poorly, or only partially fertilise them, but after a few attempts normally get things right.

At this point it’s advisable to remove all other fish except the male, or remove male and eggs elsewhere ( a small plastic container can be used to do so without harming either).

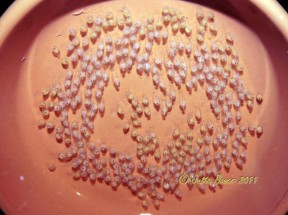

Brood size is very large with up to 450 eggs having been observed in a single batch (J. Bauer, pers. comm.), and the eggs themselves are also relatively large as with other fluvial members of the genus.

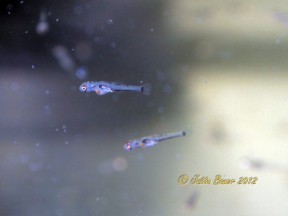

Incubation is normally 9-12 days, and fry undergo an initial pelagic stage during which they live and feed up in the water column before dropping to the substrate.

They can be offered Artemia nauplii, microworm, and similarly-sized live foods immediately.

Bear in mind that not only is this species particularly fecund but survival rate also tends to be high, so ensure you possess the facilities to raise 100-200 fry before attempting to breed it.

NotesTop ↑

This fish is normally imported alongside the congener R. candidianus and is actually the commoner of the two in the aquarium trade.

It appears very similar to R. candidianus but does not grow as large, possesses a more rounded snout, and most specimens also have spot-like markings on the sides of the head.

In addition it can be distinguished from other Taiwanese Rhinogobius species by the following combination of characters: second dorsal and anal fins without spots; cheek with numerous spots in both males and females; midline of body with a row of dark blotches; inner part of caudal-fin blue in adult male; 33-36 longitudinal scale rows; 10-12 scales between origin of first dorsal and pectoral fins.

It appears to be a member of the R. brunneus group of closely-related species within the genus of which members share the following combination of characters: predorsal naked, or with small cycloid scales, the scaled area never extending beyond the vertical of the posterior margin of the preoperculum; cheek with 2 mainly horizontal rows of sensory papillae.

In addition it may belong to an assemblage of fluvial, land-locked, non-diadromous Rhinogobious spp. which have relatively large eggs and 27-29 vertebrae.

The Gobiidae is the most speciose vertebrate family and notoriously problematic in terms of identifying fishes down to species level.

Within this sizeable assemblage Rhinogobius is often included in the subfamily Gobionellinae alongside genera such as Brachygobius, Chlamydogobius, Mugilogobius, Pseudogobiopsis, Schismatogobius, and Stigmatogobius.

Members can be told apart from these and all other gobiid genera by the following combination of characters: head with four simple, longitudinal infraorbital sensory papilla rows a, b, c, and d, single cp papilla, and paired papillae in mental row f; head canal variable from complete loss to normal development of anterior and posterior oculoscapular canals, and preopercular canals, and always with double interorbital pores λ if the pore is present; body mostly covered with ctenoid scales; longitudinal scale series 25–42; head including cheek, snout, opercle, anterior part of nape as well as pre-pectoral region all naked; D1 usually VI; D2 I, 6–11; A I, 5–11; P 14–23; and V I, 5 + I, 5, forming a rounded disc with frenum present, performing two pointed spinous lobes, the spinous ray usually longer than the first branched ray; dorsal pterygiophore formulae modally 3–22 1 101; vertebrae 25–29, usually 26 for most landlocked species.

The genus is widely-distributed throughout much of continental Asia in Russia, Korea, China, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand, plus numerous islands of the Western Pacific including Japan, Taiwan, Hainan, and the Philippines.

There currently exist over 60 recognised species with many more awaiting formal description, and a number of the described ones are only considered nominal taxa pending additional study.

Those exhibiting similarities in appearance, morphology and behaviour are therefore often aggregated in nominal species groups, e.g., the R. brunneus group, R. duospilus group, etc., for ease of reference.

The fused pelvic fins form a structure normally referred to as the ‘pelvic disc’, a common feature among gobiids which is used to adhere to rocks and other submerged surfaces.

Rhinogobius spp. also exhibit different reproductive strategies depending on environment, with those inhabiting rivers connected directly to the sea typically amphidromous, and those landlocked in upper reaches of rivers or lakes non-diadromous.

Many of those appearing in the aquarium trade have proven difficult to identify for a number of reasons including:

– taxonomic confusion.

– lack of aquarium literature.

– incorrect labelling by exporters and subsequently shops.

– historical over-use of some names, e.g., ‘Rhinogobius wui‘, currently an invalid synonym of R. duospilus.

– likely trade of undescribed species without locality data.

– mixing of species at export facilities.

Thanks to Jutta Bauer.

References

- Chen, I-S. and K.-T. Shao, 1996 - Zoological Studies 35(3): 200-214

A taxonomic review of the gobiid fish genus Rhinogobius Gill, 1859, from Taiwan, with description of three new species. - Ho, H.-C. and K.-T. Shao, 2011 - Zootaxa 2957: 1-74

Annotated checklist and type catalog of fish genera and species described from Taiwan.