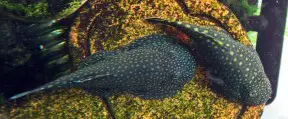

Gastromyzon scitulus

Etymology

Gastromyzon: from the Greek gaster, meaning ‘stomach’ and myzo, meaning ‘to suckle’.

scitulus: from the Latin scitulus, meaning ‘beautiful, elegant’, in allusion to this species’ attractive colour pattern.

Classification

Order: Cypriniformes Family: Gastromyzontidae

Distribution

Restricted to tributaries of the Sungai (river) Sadong basin in southern Sarawak state, Malaysian Borneo with type locality ‘Serian, Sungai Kuhas, 6.9 kilometers from Tebeu Tebakang turnoff, 5.8 kilometers inside right road, 1°09’10.0″N, 110°29″22.7″E, Sadong River basin, Sarawak, Borneo’.

All members of the genus are endemic to Borneo with over half restricted to just a single river basin or sub-basin.

Habitat

Gastromyzon spp. are obligate dwellers of swift, shallow streams containing clear, oxygen-saturated water and have been recorded from sea level to 1350 m amsl throughout hill regions of Borneo.

They typically inhabit riffles and runs and are often found above or below cascades and waterfalls.

Substrates are generally composed of gravel, rocks, boulders or bedrock carpeted with a rich biofilm formed by algae and other micro-organisms.

Aquatic plants are uncommon and while riparian vegetation may be present these loaches tend to be most abundant in partially or fully-shaded zones.

Field observations have revealed that individuals typically position themselves facing into the flow, either along the sides, behind or under rocks, their specialised morphology (see ‘Notes’) allowing them to forage and maintain a particular spot without being swept away.

In nature G. scitulus occus sympatrically with Homaloptera orthogoniata and the congener Gastromyzon zebrinus.

Maximum Standard Length

40 – 45 mm.

Aquarium SizeTop ↑

An aquarium with base dimensions of 75 ∗ 30 cm is large enough to house a group.

Maintenance

Most importantly the water must be clean and well-oxygenated so we suggest the use of an over-sized filter as a minimum requirement.

Turnover should ideally be 10-15 times per hour so additional powerheads, airstones, etc. should also be employed as necessary.

Base substrate can either be of gravel, sand or a mixture of both to which should be added a layer of water-worn rocks and pebbles of varying sizes.

Aged driftwood can also be used but avoid new pieces since these usually leach tannins that discolour the water and reduce the effectiveness of artificial lighting, an unwanted side-effect since the latter should be strong to promote the growth of algae and associated microorganisms.

Exposed filter sponges will also be grazed, and some enthusiasts maintain an open filter in the tank specifically to provide an additional food source.

Although rarely a feature of the natural habitat aquatic plants can be used with adaptable genera such as Microsorum, Crinum and Anubias spp. likely to fare best. The latter are particularly useful as their leaves tend to attract algal growth and provide additional cover.

Since it needs stable water conditions and feeds on biofilm this species should never be added to a biologically immature set-up, and a tightly-fitting cover is necessary since it can literally climb glass.

Water Conditions

Temperature: For general care 20 – 24 °C is recommended but it can withstand warmer conditions provided dissolved oxygen levels are maintained.

pH: 6.0 – 7.5

Hardness: 18 – 215 ppm

Diet

Much of the natural diet is likely to be composed of benthic algae plus associated micro-organisms which are rasped from solid surfaces.

In captivity it will accept good-quality dried foods and meatier items like live or frozen bloodworm but may suffer internal problems if the diet contains excessive protein.

Home-made foods using a mixture of natural ingredients bound with gelatin are very useful since they can be tailored to contain a high proportion of fresh vegetables, Spirulina and similar ingredients.

For long-term success it’s best to provide a mature aquarium with a plentiful supply of algae-covered rocks and other surfaces.

If unable to grow sufficient algae in the main tank or you have a community containing numerous herbivorous fishes which consume what’s available quickly it may be necessary to maintain a separate tank in which to grow algae on rocks and switch them with those in the main tank on a cyclical basis.

Such a ‘nursery‘ doesn’t have to be very large, requires only strong lighting and in sunny climates can be kept outdoors. Algal type is also important with diatoms and softer, green varieties preferred to tougher types such as rhodophytic ‘black brush’ algae.

Gastromyzontids are often seen on sale in an emaciated state which can be difficult to correct. A good dealer will have done something about this prior to sale but if you decide to take a chance with severely weakened specimens they’ll initially require a constant source of suitable foods in the absence of competitors if they’re to recover.

Behaviour and CompatibilityTop ↑

Very peaceful although its environmental requirements limit the selection of suitable tankmates somewhat, plus it should not be housed with any much larger, more aggressive, territorial or otherwise competitive fishes.

Potential options include small, pelagic cyprinids such as Tanichthys, Danio, and Rasbora, stream-dwelling gobies from the genera Rhinogobius, Sicyopterus, and Stiphodon, plus rheophilic catfishes like Glyptothorax, Akysis and Hara spp.

Some loaches from the families Nemacheilidae, Balitoridae and Gastromyzontidae are also suitable but others are not so be sure to research your choices thoroughly before purchase.

Gastromyzon spp. tend to exist in loose aggregations in nature so buy a group of 4 or more if you want to see their most interesting behaviour.

They’re territorial to an extent with some individuals appearing more protective of their space than others, often a prime feeding spot.

Sexual Dimorphism

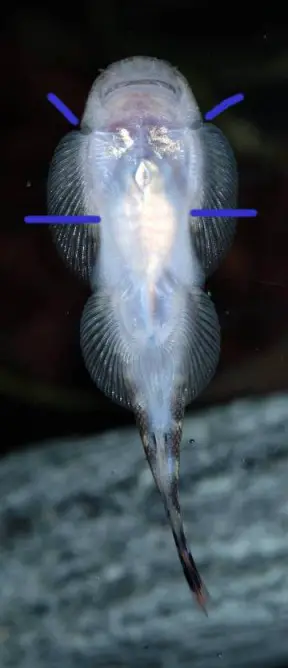

Adult females are noticeably heavier-bodied and often a little larger than males; these differences are more apparent when viewing the fish from above or below.

Reproduction

Observations were made by German aquarist Philipp Dickmann and published in a hobbyist magazine during 2001.

He collected wild specimens of both G. scitulus (identified as G. punctulatus at the time) and G. monticola, and attempted to spawn both using different methods.

Initially a pair of G. scitulus were placed in a 30 litre tank without substrate or filtration but heavily-aerated and containing some broken flower pots, boulders and floating plants for cover.

These were offered a rich diet with plenty of live and frozen mosquito larvae to bring them into breeding condition.

The temperature was then raised to 82.4°F/28°C over a period of 8 weeks and feeding increased; these conditions were maintained for 3 weeks during which the temperature unintentionally rose to 89.6°F/32°C.

After courtship behaviour was observed cool water changes were conducted to bring water temperature down to 77°F/25°C and the fish spawned during a period of low air pressure; at the point of climax their bodies are depicted to interlock away from the substrate.

At least 100 tiny (diameter <1 mm), sinking, non-adhesive eggs were observed and at this point the adults were removed.

The eggs began to hatch in around 3 days and the fry were initially photophobic and required an infusoria–type diet due to their small size (~3 mm SL). Apparently the plants in the tank began to rot resulting in a loss of water quality and after 3 weeks all the fry were dead.

More success was had with G. monticola, this time using a 160 litre tank with a coarse gravel substrate, some pieces of slate propped up against the rear pane, a clump of a Cryptocoryne sp. and a piece of driftwood.

Water temperature was maintained at 75.2°F/24°C and GH was 10-12°. This was again unfiltered but heavily-aerated with Ambastaia sidthimunki, Pangio sp. and a large population of the burrowing snail Melanoides tuberculata also in residence.

On this occasion small numbers of fry simply began to appear over time, and spawning was observed continuously over a period of 12 months.

NotesTop ↑

One of the more commonly-traded members of the genus and often found in mixed shipments which may contain other Gastromyzon spp. or related fishes like Beaufortia kweichowensis. These are typically labelled as ‘Borneo sucker’, ‘Hong Kong pleco’, ‘butterfly loach’, etc., regardless of species.

It’s sometimes misidentified as G. punctulatus, a species not currently traded which possesses yellow finnage and a lighter-coloured, less-intensely spotted body.

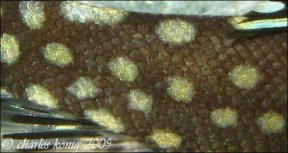

It can be distinguished from congeners by the following combination of characters: gill slit angular; presence of subopercular groove, running continuous to origin of pectoral-fin; body black with numerous, small, evenly-spaced light brown spots; head dorsum black with numerous cream spots; pectoral and pelvic fins with cream spots; caudal-fin with iridescent blue streaks in life; presence of sublacrymal groove; snout sloping strongly from eye to tip, with rounded shape when viewed dorsally; absence of secondary rostrum; absence of postoral pouch; no scales on abdomen; 57-58 lateral line scales; pelvic-fin just reaching anal-fin origin; adpressed dorsal-fin just reaching level of anal-fin origin.

Gastromyzon spp. are placed into various species groups (putative assemblages of species which may or may not be monophyletic) for ease of reference, and G. ctenocephalus is included in the G. ctenocephalus group alongside G. scitulus.

These are defined by a combination of characters including a body pattern consisting of evenly-distributed cream spots, small adult size (< 40 mm SL), an angular gill slit and only few, large, non-branching papillae in the lower lip.

G. scitulus sensu stricto can be told apart from G. ctenocephalus sensu stricto by absence of blue spots in the dorsal-fin (vs. presence), 3 cream spots at the base of the dorsal fin (vs. 4-5) and a suite of morphological characters including less pectoral-fin rays (average 25 vs. 28), less pelvic-fin rays (average 17 vs, 19) and less lateral scales (average 58 vs. 60).

It also tends to have fewer, relatively larger cream spots on the body than G. ctenocephalus, especially on the dorsal surface, and the body itself has a lighter base colour.

However there exist numerous intermediate forms of both species with anomalies in otherwise typical G. scitulus specimens including darker body colour, smaller body spots, red markings at the caudal-fin edges, blue pigmentation in the dorsal-fin or yellow at the dorsal-fin base.

Whether these represent different populations of a single species or not remains unconfirmed at present, and some of them are very similar to G. ctenocephalus, meaning identification can sometimes be tricky.

In fact G. ctenocephalus and G. scitulus represent one of 12 pairs of ‘cryptospecies’ known in the genus. Cryptospecies are defined as morphologically similar, but reproductively isolated species which in fishes often inhabit adjacent river basins but in some cases occur sympatrically.

The phenomenon may be a result of parallel evolution, and is not normally considered to represent an early stage of speciation, though in the case of G. scitulus and G. ctenocephalus the opposite may be true, i.e., they may have diverged from one another quite recently, in which case they would be more accurately referred to as ‘sibling‘ species.

The current arrangement of species groups is as follows:

G. borneensis group: G. borneensis, G. monticola, G. ornaticauda, G. cranbrooki, G. cornusaccus, G. extrorsus, G. introrsus, G. bario.

G. punctulatus group: G. aeroides, G. punctulatus, G. katibasensis.

G. fasciatus group: G. fasciatus, G. praestans.

G. contractus group: G. contractus, G. megalepis, G. umbrus.

G. ctenocephalus group: G. ctenocephalus, G. scitulus.

G. lepidogaster group: G. lepidogaster, G. psiloetron.

G. ridens group: G. ridens, G. crenastus, G. stellatus, G. zebrinus.

G. danumensis group: G. danumensis, G. aequabilis, G. ingeri.

G. pariclavis group: G. pariclavis, G. embalohensis, G. venustus, G. spectabilis, G. russulus, G. viriosus.

G. ocellatus group: G. ocellatus, G. farragus.

G. auronigrus group: G. auronigrus.

Gastromyzon spp. have specialised morphology adapted to life in fast-flowing water. The paired fins are orientated horizontally, head and body flattened, and pelvic fins fused together.

These features form a powerful sucking cup which allows the fish to cling tightly to solid surfaces. The ability to swim in open water is greatly reduced and they instead ‘crawl’ their way over and under rocks.

The family Gastromyzontidae is currently considered valid as per Kottelat (2012).

It contains a number of genera which had formerly been included in several families and subfamilies, most recently Balitoridae, of which the most well-known in the aquarium hobby include Beaufortia, Formosania, Gastromyzon, Pseudogastromyzon, Hypergastromyzon, Liniparhomaloptera, Sewellia, and Vanmanenia.

References

- Tan, H.H. and C.U.M. Leh, 2006 - Zootaxa 1126: 1-19

Three new species of Gastromyzon (Teleostei: Balitoridae) from southern Sarawak. - Inger, R. F. and P. K. Chin, 1961 - Copeia 1961(2): 166-176

The Bornean cyprinoid fishes of the genus Gastromyzon Günther. - Kottelat, M., 2012 - Raffles Bulletin of Zoology Supplement 26: 1-199

Conspectus cobitidum: an inventory of the loaches of the world (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cobitoidei). - Rachmatika, I., 1998 - Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 46(2): 651-659.

Gastromyzon embalohensis, a new species of sucker loach (Teleostei: Balitoridae) from the Bentuang Karimun National Park, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. - Tan, H. H., 2006 - Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu: 1-245

The Borneo suckers. Revision of the Torrent Loaches of Borneo (Balitoridae: Gastromyzon, Neogastromyzon). - Tan, H. H. and K. M. Martin-Smith, 1998 - Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 46(2): 361-371

Two new species of Gastromyzon (Teleostei: Balitoridae) from the Kuamut headwaters, Kinabatangan basin, Sabah, Malaysia. - Tan, H. H. and Z. H. Sulaiman, 2006 - Zootaxa 1117: 1-19

Three new species of Gastromyzon (Teleostei: Balitoridae) from the Temburong River basin, Brunei Darussalam, Borneo.